So here for your reading pleasure is an excerpt on that subject from my memoir Heaven Without Her. It's not short, but then we can't capture a scientist's attention with a few high-level claims; for them, the proof's in the details.

***

It was a Friday afternoon in late autumn, 2003. A girlfriend I’ll call Anne and I had played hooky to get in one more round of golf before the weather turned. We’d already lost several balls amidst all the falling leaves, and if we got too close to the garbage containers the bees swarmed us. But the course – Western Lakes, one of my favorites – wasn’t all that busy and we’d been allowed to go out alone. Besides, it was a heartbreakingly perfect Indian summer day; the warm, moist air bore just a hint of the chill that was to come, a hint that transported me back to childhood anticipation of Thanksgiving and Christmas and endless joy.

We were on the tenth tee box when Anne made a shocking statement.

“So you’ve come to the conclusion that there’s a supreme being,” she said.

“Why, yes, I have,” I said. “An Intelligent Designer, aka God.” I was blown away that this topic had been broached by a woman whose scientific education and life’s work had left her hostile to anything smacking of religion.

She busied herself with a few practice swings.

“There are only two explanations for our origins,” I added, unable to bear her silence. “A God or time plus chance, as in evolution. I studied it, and I’m certain the answer is a God.”

“Prove it.”

Prove it? Atheist Anne was interested in hearing evidence for God? I was thrilled; I wanted nothing more than to tell her about the incredible truths I had discovered.

“You want the five-minute tour or an hour-long lecture?”

“Puh-leeze,” she said, teeing up her ball. “I listened to enough lectures in school. Just give me the CliffsNotes version.”

She hit her shot an impossible distance, maybe a couple hundred yards. Even though it had sailed a bit right on her, into the fringe, it would take me at least two shots to catch up.

“Five-minute version, coming right up,” I said, teeing up my Golden Girl and hitting it about 100 yards, straight down the middle. I used the moments of silence to quickly rifle through the “science” files in my head. By that time, I’d collected overwhelming proof against evolution theory, having listened to scores of lectures and read more than a dozen books on the subject. I could tell her with a fair amount of confidence about the origins implications of everything from genetics and geological formations to paleontology and sedimentology.

But Anne was a big-corporation manager who based her decisions on high-level information, not details; I needed to pick just a few of the points that would be most eye-popping to her.

Ah, here, filed under “M” not far from “magnificent…”

“First, mutations,” I said, climbing into the cart as she stomped on the accelerator. “Mutations that actually add to a creature’s genetic information. Evolution can’t function without them.”

“True enough,” she said.

“They don’t exist. Name one.”

“Come on, that’s not my field. You should ask an expert. Hit your ball.”

I climbed out of the cart and slapped it with my 7 wood, the only fairway wood I seemed to be able to hit more than 15 feet. My Golden Girl formed a perfect little arc and landed another 100 yards closer to the green. It sat prettily in the middle of the fairway to the left of Anne’s tee shot.

“Cart golf,” I said, jumping back in. “I did ask an expert. I emailed the head of the federal government’s human genome project and asked him for one example of a positive, additive genetic mutation.”

“What did he say?”

“He didn’t have an answer for me.”

She used her 8 iron to loft her ball onto the green; amazingly, I achieved the same result with my trusty 7 wood.

“Did he answer you at all?”

“Immediately. He said people with sickle cell anemia don’t tend to get malaria.”

“Well, there you go.”

“Not quite,” I said. “It may be positive for the person with sickle cell anemia, of course, but it’s not an additive mutation. It doesn’t add anything to the DNA, which is what would be required if, for instance, a dinosaur were to sprout wing stubs on its species’ way to becoming a bird.”

She shrugged. “Then if that was the best this guy could do – well, he’s probably just an administrator.”

“M.D. and Ph.D. He’s a chemist and a geneticist.”

She shrugged again and headed for the green with her putter.

We finished out the hole (she with a par, me with a double bogie) and headed to the next hole. A foursome was just teeing off, and from the first one’s pathetic drive, it looked like we might have a long wait before we could tee off.

“Okay, I’ll grant you that makes some sense,” Anne said, picking up the conversation where we’d left it at the 10th green. “Strike one against evolution. What else have you got?”

The second golfer had teed up by that time, buying me a few moments of silence to return to my mental file cabinet. “Irrefutable” was the word that popped into my head – and indeed, there was my answer right next to it, straight out of biochemist Michael Behe’s mind-blowing book Darwin’s Black Box.

“Irreducible complexity,” I said as soon as the golfer had connected with her ball, sending it out a good 25 yards from the tee box. I had no idea if Dr. Behe’s line of thought would impress Anne, but his book had blown me away. “The fact that biological systems are too complex to have been formed through bunches of tiny little modifications.”

“Too complex? Or too complex for you and these authors you’re reading?”

“Too complex period,” I said, praying for the wisdom to capture this subject in a few sentences. Her question reflected evolutionists’ portrayal of Intelligent Design advocates as too dumb to understand, and too cowardly to even try. “The book I read on this was written by a biochemist, so I’d say he understood the subject pretty well.”

“Geez, we’re going to be here forever,” Anne said, waving her gloved hand towards the tee box, where a golfer in bright aqua shorts had just completed her second total whiff of the ball.

“We could ask if they’d let us play through,” I said, wishing they’d take notice of their pokiness and wave us through without being asked.

“That’s okay. We’re not in any hurry, are we?”

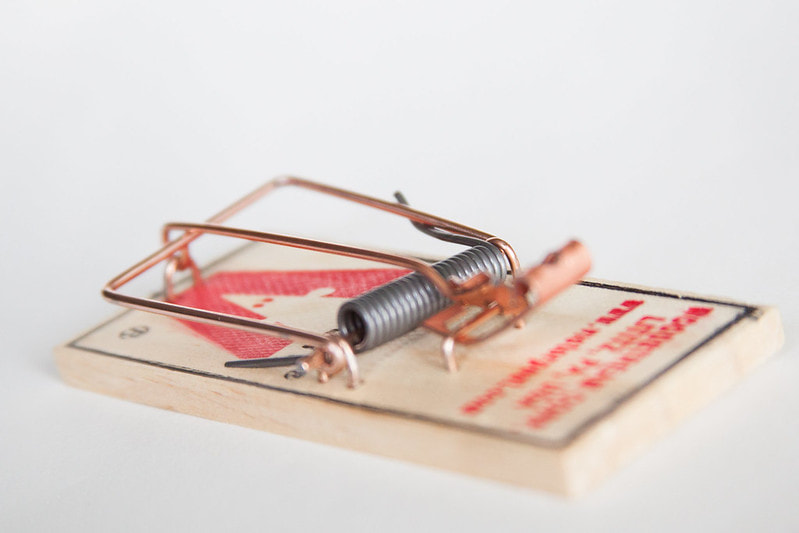

“Not me,” I said, popping open the Diet Pepsi I’d picked up at the turn and taking a good swig. “So – irreducible complexity. Consider, if you will, the lowly mousetrap. Platform, hammer, spring, catch, and a holding bar.”

She rolled her eyes at me and smiled wickedly. “You don’t think it’s odd that you know the parts of a mousetrap? You, who would do anything to avoid ever having to touch one?”

I had to laugh. “But reading about it isn’t so bad. Anyway, it has these five parts. It can’t function without all five of them.”

She thought for a moment. “Right – I can see that.”

“That makes it an irreducibly complex system. If it were a living system, it could not have evolved component by component. Without all of these interdependent parts in place, none of them would’ve functioned, and none would have survived the natural selection process. Make sense?”

Anne considered this for a few ticks and nodded. “Okay. I can buy that.”

I took a deep breath. I’d always been afraid of Anne; she’s one of these very frank people who thinks it’s her duty to tell you if you’re being an idiot, and I don’t usually appreciate hearing that. Besides, I’ve never been articulate, and this aging brain of mine is beginning to betray me now and then. A potentially lethal combination for someone intent on making a mission-critical point, as we say in the ad biz.

But I could hardly quit now.

“Well, what Dr. Behe did,” I said, “was show how human systems are irreducibly complex and so could not have evolved. He described a handful of them in some detail – blood coagulation, cell operation, and the immune system, for instance. He showed how these things could not have come about by gradual evolution of interdependent parts, and how they had to have been designed as complete systems from the start.”

Anne was watching the fourth golfer tee off. It looked like she was lost in space. She wasn’t, though; I knew she was thinking about what I’d said.

“Eyes,” she said. “I’ve heard that argument applied to eyes. Something about some ancient fossil having incredibly complex eyes.”

I tried not to show my surprise that she’d paid a lick of attention to this sort of information.

“I’ve read that, too,” I said. “Trilobites, maybe? Something like that, anyway. If evolutionists are to be believed, they were among the earliest creatures and went extinct hundreds of millions of years ago – yet they had these amazingly complex, multi-lensed eyes that let them see underwater without any distortion.”

“Yes, I think that was it, and there’s no evidence of precursors.” She was putty in my hands, it seemed – except apparently she couldn’t quite leave what she’d always been taught: “That they’ve found so far, at least.”

It was finally time to tee off, and the slow foursome ahead of us stood back to let us play through. Whereupon we both duffed our drives, which led to friendly laughter and chatter all around as we worked our way down the fairway.

I decided to let the subject of origins ride for the duration. Like most of my friends, Anne already thought I’d gone off the deep end on this God thing, and I wanted to prove I was still a real person interested in the real world. We chatted about work and vacations, clothes and movies.

But she brought it up again as we approached the Par 3 17th hole.

“So you don’t deny natural selection,” she said out of the blue, surprising me again.

“Not at all,” I said. Were we really having this conversation? “It happens; it’s like a manufacturer’s quality control system, except it occurs without man’s intervention. It happens artificially, too, which is why there are hundreds of breeds of dogs today. Certain genetic traits are kept, others are bred out.”

“I thought creationists – that’s what you are, right? -- I thought creationists denied that sort of evolution fundamental.” She parked the cart and marched over to the tee box, squinting at the flag just 112 yards away.

“I’m pretty sure it predates Darwin,” I said, smiling at the understatement. “In fact, the first book in the Bible – Genesis – records artificial selection in some sort of livestock.”

She looked back at me, her eyebrows raised in surprise.

“Really, it does,” I said, aware that I was in danger of drifting. “It’s what they call ‘microevolution.’ Whereas when evolutionists say we evolved from slime, they’re actually talking about macroevolution – that’s what creationists deny. It’s bait and switch – they use real-life examples to get you to agree to microevolution, then say that it explains macroevolution. Pretty deceptive, if you ask me.”

I re-focused my thoughts on the main point of today’s discussion: showing Anne there’s good reason for believing that this universe is the work of an Intelligent Designer in general; I’d save the God-of-the-Bible evidence for another day.

“But the point is that natural selection describes the survival of the fittest,” I said, grateful to whoever had come up with this easy-to-remember way of explaining a critical distinction. “It can’t describe the arrival of the fittest. It isn’t a creative process.”

She teed off then, using an iron. Her ball landed about an inch from the hole, causing a group of grounds workers who’d gathered on the last green to erupt in cheers.

--Heaven Without Her, pages 114-121

RSS Feed

RSS Feed