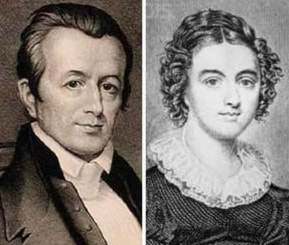

First published by Arabella Stuart in 1855, Lives of the Three Mrs. Judsons uses multiple sources (in particular, their letters to friends and loved ones) to paint astounding portraits of three remarkable women—women who, one after the other, helped their beloved Adoniram bring the gospel to the people of Burma in the first half of the 19th century.

This was not a call to luxury.

In the first place, the trip from New England to Burma, via India, took literally months, mostly with no land in sight, via ships we 21st century creampuffs would never set foot on. And once there, they found the accommodations primitive, the climate oppressive, the government often brutal, and the medical care practically non-existent, with no one to help them deal with the illnesses that frequently assailed them and their precious children.

The Burman people were not unfriendly, but for a long time, communicating with them was next to impossible. Adoniram and the first Mrs. Judson, Ann, had to learn a new language, complete with a new alphabet; To the Golden Shore shows pages of their writing in this strange new tongue, and it looked to me like a bunch of circles piling up on one another.

I don’t know which of the three Mrs. Judsons had the most difficult time.

It was Ann who saw Adoniram spending months in a ghastly jail, being hung upside down by shackles night after night. She had to beg, borrow and steal access to him in order to bring him food and consolation—and, eventually, to smuggle in his Burmese Bible translation-in-process for safekeeping against increasingly hostile Burman officials.

The circumstances of Ann and Adoniram’s lives together were horrible by any standards. Yet apparently she did not seek relief from these trials. Instead, as she wrote in a letter home towards the end of her life, “The anguish, the agony of mind, resulting from a thousand little circumstances impossible to delineate on paper, can be known by those only who have been in similar situations. Pray for us, my dear brother and sister, that these heavy afflictions may not be in vain, but may be blessed to our spiritual good, and the advancement of Christ’s church among the heathen.” (Page 78)

Ann died in 1826, leaving a broken-hearted Adoniram to carry on alone. But in 1834, he married Sarah, the widow of George Boardman. The Boardmans had been missionaries to the Karen people, and Sarah stayed in Burma to continue this work after George’s death in 1831.

The cruel trials continued for the second Mrs. Judson, with Adoniram’s failing health being the most painful.

But Sarah was never without comfort. As she wrote to her husband when he was sent off on a long sea voyage to treat a severe cough, “I hope I do not feel unwilling that our Heavenly Father should do as he thinks best with us; but my heart shrinks from the prospect of living in this dark, sinful, friendless world, without you … But the most satisfactory view is to look away to that blissful world, where separations are unknown. There, my beloved Judson, we shall surely meet each other; and we shall also meet many loved ones who have gone before us to that haven of rest.” (Page 140)

As it turned out, Adoniram recovered from this illness. It was Sarah whose health would soon begin to fail. She died in 1845, en route to America for medical treatment.

Adoniram married a third time the following year. His new wife was Emily Chubbock, a writer whom he commissioned to write a biography of Sarah. Her Memoirs of Mrs. Sarah B. Judson was published in 1850; her husband was pleased with the manuscript, she said, and she cared little whether anyone else liked it.

The third Mrs. Judson also fell gravely ill in the mission field. It was then that she wrote a poem entitled “Love’s Last Wish,” which included these lines:

“Thou say’st I’m fading day by day,

And in thy face I read thy fears;

It would be hard to pass away

So soon, and leave thee to thy tears.

I hoped to linger by thy side,

Until thy homeward call was given,

Then silent to my pillow glide,

And wake upon thy breast in heaven.”

Emily recovered, however, and her wish to outlive Adoniram was granted. “Closing Scenes in the Life of Dr. Judson,” her moving account of his last days and his 1850 death, is reprinted in Lives of the Three Mrs. Judsons (pages 154-161)—as is an excerpt from her poem, “To My Husband” (page 167):

“Here closely nestled by thy side,

Thy arm around me thrown,

I ask no more. In mirth and pride

I’ve stood—oh so alone!

Now, what is all this world to me,

Since I have found my world in thee?

“Oh if we are so happy here,

Amid our toils and pains,

With thronging cares and dangers near

And marr’d by earthly stains,

How great must be the compass given

Our souls, to bear the bliss of heaven!”

Oh, to have the eternal eyes of these three women! But reading about them, as well as scores of others featured in biographies and books on Christian history, has at least shown me that it is possible to truly live for Christ, and for eternity. May we all learn to do just that.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed