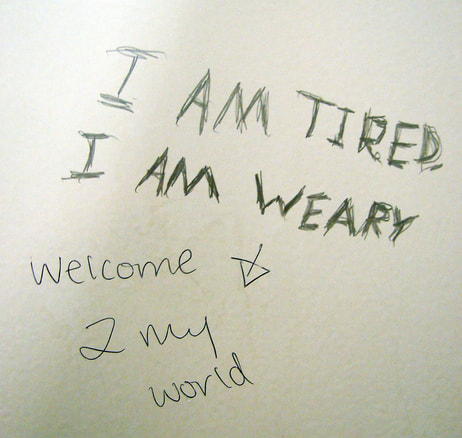

As I type these words, I’m getting flashes of my own predilection for complaining: Yesterday's traffic was monstrous, I’m so tired of winter, the dog kept me awake half the night, there’s cilantro in my salad – you name it, I can come up with a complaint.

It’s a habit I’d better begin eliminating immediately. Because while my life is full to overflowing right now, if I live long enough there may come a time when I’m facing hour after empty hour. And if I’d like to fill at least some of them with unpaid companionship, I’d best learn to be a source of happiness to others.

I’m reminded of this every time I visit friends at the nursing home. Just about everyone living there for the duration has some measure of trial and sorrow in his or her life. Some may have more pain than their neighbors, others may be more disabled physically or mentally, and many have outlived all their friends and relatives. Yet such circumstances seem to have little impact on where these individuals land on the happiness index; some wallow in misery, while others radiate joy, regardless of their personal tribulations.

To make sure I’m not offending anyone, I'll use some examples from the way-distant past.

A woman I’ll call Gladys always seemed to be a happy camper. She was 98 when I met her. Childless and widowed, her mind was no longer as sharp as it must have been once upon a time, but we always had wonderful visits. She liked to talk about God and gardening, about the perfectly lovely food she was enjoying here, about this or that aide who had gone out of her way to be kind to her next door neighbor that morning, about the beauty of the spring blooms or autumn leaves or pristine snow outside her window.

Gladys and I also talked at length about the good old days. When asked, she didn’t mind sharing experiences from her past. But she was never self-focused. Even though her short-term memory was often on the fritz, she always managed to ask me about something important in my life, from our progress with a kitchen remodel to the health of a sick old dog. How she managed to recall such details week after week, I'll never know. Perhaps she jotted down a few notes after I left, and reviewed them just before my regular weekly visit. Or perhaps she asked the Lord to help her remember.

You can probably understand why I loved visiting Gladys, and how sad I was to learn one day that she had died. There was no drama in her departure: One night she’d simply gone to bed with “a little stomach ache,” and never woke up. This surprised no one. She hadn't been one to complain about her health. I even commented on that once; she said that she would have to be one ungrateful old lady to complain about anything in light of all the blessings the good Lord had showered on her throughout her life.

Then there was Clara, 87 when I met her.

Clara was one of the most unhappy women I’ve ever known. A professing but apparently non-practicing Christian, she too was widowed. But unlike Gladys, Clara had two children – a son who dropped in for a quick visit every week, and a daughter who showed up once or twice a year.

I could certainly understand the daughter’s point of view. With Clara, the complaints started before you even put your purse down, and ended only as you were walking out the door. Look at the messy job her aide had done with her bed this morning! You wouldn’t believe the slop they had served in the dining room this week! Old Eva across the hall snored all night long again! Wouldn’t you think someone with half a brain would come visit her now and then?

Surely Clara said something nice about someone in the four years I visited her, week after miserable week. But I honestly can’t think of a single example. I can’t even remember her smile; it’s quite possible that I never saw it.

Clara died a long and lingering death, having given anyone who would listen a detailed play-by-play of her illness for the last three years of her life. I went to her funeral at a nearby cemetery. There were 50 seats in the hall she’d chosen for her service, the same hall that had been packed for her husband’s funeral five years earlier. Alas, this time there were only four of us in attendance: her son, her daughter and son-in-law, and me.

Sadly, people like Clara are often bitter to the bone. There is hope for them, of course – but they have to be willing to acknowledge their own imperfections, to repent, and to receive the free gift of eternal life. Then, prepare to be blessed: Complaints seem to be few and far between from those who are pointed toward a glorious eternity!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed