But I didn’t want to close this chapter on my mania without highlighting a fascinating passage from Lives of the Three Mrs. Judsons, published in 1855—a passage that underscores the fundamental difference between Christianity and man-made religion. Here, on pages 20-25, author Arabella Stuart provides a fabulous description of the allegedly impregnable Buddhism that Adoniram and first wife Ann encountered when they arrived in Burma.

Some excerpts:

“A curious feature of Buddhism is that one of the highest motives it presents to its followers is the ‘obtaining of merit.’ Merit is obtained by avoiding sins, such as theft, lying, intoxication, and the like; and by practicing virtues and doing good works. The most meritorious of all good works is to make an idol; the next to build a pagoda … If they give alms, or treat animals kindly, or repeat prayers, or do any other good deed, they do it entirely with this mercenary view of obtaining merit.”

Why, one might ask, would a Buddhist want to obtain merit? Stuart tells us:

“This ‘merit’ is not so much to procure them happiness in another world, as to secure them from suffering in their future transmigrations in this; for they believe that the soul of one who dies without have laid up any merit will have to pass into the body of some mean reptile or insect, and from that to another, through hundreds of changes, perhaps, before it will be allowed again to take the form of man.”

Granted, it seems a silly worldview, especially since there’s absolutely no evidence that it’s true. But if everyone is working towards the goal of not waking up as a cockroach in the next life, at least it must make for a loving and selfless culture?

Not exactly, according to Stuart:

“This reliance on ‘merit,’ and certainty of obtaining it through prescribed methods, fosters their conceit, so that ignorant and debased as they are, there is scarcely a nation more offensively proud. It also renders them entirely incapable of doing or appreciating a disinterested action, or of feeling such a sentiment as gratitude. If you do them a favor, they suppose you do it to obtain merit for yourself, and of course feel no obligation to you.”

The result?

“The simple phrase, ‘I thank you,’ is unknown in their language.”

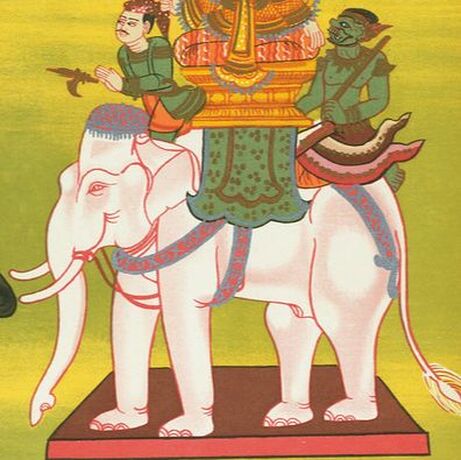

Stuart goes on to quote the Foreign Quarterly Review, which reported that the highest rank to which a Buddhist can obtain is “no other than that diseased animal, the White Elephant.” This creature supposedly houses “a blessed soul of some human being, which has arrived at the last stage of the many millions of transmigrations it was doomed to undergo, and which, when it escapes, will be absorbed into the essence of the Deity.”

Stuart concludes her account thusly:

“Such was the stupendous system of superstition and ignorance, which two feeble missionaries armed like David when he met the Philistine with ‘trust in the Lord his God,’ ventured to attack, and hoped to subdue.”

For many Burmese, this trust was enough. When he died in 1850, Adoniram Judson left behind more than 8000 Burmese converts to Christianity. And thanks in large part to his work, today there are over 4 million believers in Burma (now Myanmar)—approaching 10% of the population (per Christian History, Issue 90, Spring 2006, pages 35-37). That’s an enormous army of men and women who have turned from wishing on White Elephants to trusting in the Lord Jesus Christ.

And just think: as believers ourselves, one happy day we’ll get to hear, first-hand, precisely how He set them free!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed